Brian Dagenais is an enigma. How does a person who was a longterm employee in a highly structured environment (the payday lending industry) become a successful real estate investor, futuristic developer and out-there entrepreneur by age 44? It’s a mystery, and even though I’ve known Brian for years and I interviewed him for this article for 90 minutes, I can’t say that I am truly any closer to figuring this out.

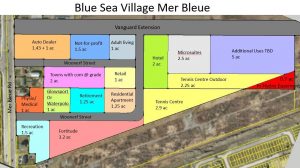

Mr. Dagenais and his BlackSheep Developments group recently purchased nearly 14 acres in Orleans (later expanded to 38 acres) where they are developing a project called “Blue Sea Village Mer Bleue.” It’s a mixed-use development and at its heart will sit a Douglas Cardinal-designed masterpiece, an indescribable 100,000 square foot building called “Fortitude.” Since it’s indescribable, I won’t try; instead, here’s an elevation:

That tower you see in the above photo is a 2-storey sports bar that towers 30 metres above the Mer Bleue plain, accessible not only by elevator but also by a feature stair, so you can at least get some exercise before chowing down on some hearty eats. It’s Orleans’ very own Grouse Grind.

Fortitude will house: A 2,000-person gymnastics club, an obstacle course, a dance studio, food and beverage services, physiotherapy clinic, chiropractor, tech store, spa and hair salon, sports bar, music studio, restaurant, health food store, juice bar, yoga studio, diet centre, sports apparel, acupuncture clinic, and registered massage therapy. It’s the single most popular project I’ve seen since my days with the Ottawa Senators in the early 1990s.

Like the design of Canadian Tire Centre, services are deployed around the skin of the building with institutional uses (like gymnastics) housed in its interior, which means they can be double-loaded. That is, they’ll have doors and windows on two sides—the first to the wider world, and second, to the interior. As a result, for example, the restaurant on the ground floor can have its own outdoor space for a patio, even a games area, while people inside will still be able to access it from the interior of the building.

Having independent ingress and egress adds more life to a neighborhood and makes each tenant generally more successful.

Visits to the new village will exceed one million a year and quite possibly two million. Jobs estimates for the entire development (including the adjacent property of 24 acres) are in the order of 2,880 FTEs or full-time equivalents.

Projects like this used to require significant government funding, but today a commercial “apron” of retail and other uses wraps around institutional ones meaning they (not government) subsidize the social good on a sustainable, on-going basis. Why would they do that? Because they want to be near and benefit from traffic generated by the gymnastics club as well as other institutional uses.

Here’s a sneak peak of their (preliminary) concept plan—

The BlackSheep group are also proposing (for what I believe is the first time in Ottawa-Gatineau) to include woonerf streets, a Dutch term meaning “living” roads. Essentially, these are streets that prioritize pedestrians and bicycles over cars.

Here’s an image of what a woonerf roadway looks like from Dutch Wikipedia:

[Source: Erauch, Nederlands Woonerf (Dan Burden), 15 November 2004]

Cars are welcome, but they are guests or as American clergyman Douglas Horton once said, “Drive slow and enjoy the scenery [or] drive fast and join the scenery.”

Needless to say, city of Ottawa planners and traffic engineers as well as plans inspectors have a lot to digest with this development. Firstly, they tend to prioritize industrial jobs over, say, gymnastics coaches. Secondly, they prefer roadways that are 40 metres wide and can sustain Formula One level speeds for cars, buses and trucks. Thirdly, they typically struggle with mixed use development, preferring zoning regulations that insist on places that are either all residential or all commercial or all industrial, meaning that very trip is a car trip, and nothing is walkable. And finally, they may have a tough time with a green roof and other measures taken to reduce the environmental footprint of the development. Still, one can always hope.

And that is where Brian Dagenais and his group are—they’re trying to revolutionize not only how the sports training industry is housed, but also how development is done in Ottawa.

Brian got his start in real estate inadvertently—his first wife was not prepared to accept living in a rented home. Given that he was working in a position that did not pay especially well (he was making $12 per hour at the time), Brian looked around for something inexpensive. He found it in Vanier—a triplex where he and his bride could live and where rent from the other two apartments would help them pay their mortgage.

Everyone told Brian Vanier was the wrong place to invest and to live, but he is (like so many entrepreneurs) a contrarian and stubborn. He plowed ahead despite the fact that Vanier was ranked in the bottom five places to live in Ottawa.

Then, after seeing how fast values were climbing in the area and how much gentrification was happening around him, he got the real estate bug. Before long he had a highly animated portfolio of 32 doors, producing above average income.

“We bought that triplex in August of 2000 for $136,000 under a power of sale (the somewhat friendlier Canadian equivalent to a foreclosure in the US). Then I found out from a realtor six months later that it was worth $200,000 more than we paid—a spectacular gain. But we didn’t sell it; we refinanced it, took that money out tax free and bought more… a lot more property. It was a ‘rinse and repeat’ kind of thing,” Mr. Dagenais says.

When I ask Brian about “profit,” often a dirty word to Canadians, he adds this, “Most Canucks think that profits are achieved through slickness or by outsmarting someone. And we tend to celebrate money that is won rather than earned like, for example, when a person wins a lottery or inherits a pile of money. It makes me cringe when I see a film like The Wolf of Wall Street because they push the idea that business people don’t create any value—they simply separate you from your money. It ignores many small business owners who work incredibly hard to make a living and are the backbone of a civil society, at least in my view.”

Anyway, after leaving his job, his portfolio-building work accelerated, and he turned to development as well.

The real estate industry in Ottawa suffers in the shadow of a more glamorous field like tech or a more predictable area like, say, employment in government. The industry faces a crisis in terms of the aging-out of its members—whether they are developers, architects, designers, investors, financiers, mortgage brokers, realtors and so forth. Hence, there is ample opportunity for younger folks to enter. I mean, people still need places to live, work, entertain, learn, gather, play, make, create and shop, right?

Bruce M. Firestone is a founder of the Ottawa Senators, a Century 21 Explorer Realty broker, real estate investor and business coach. Follow him on Twitter @ProfBruce or email him at bruce.firestone@century21.ca.

Session expired

Please log in again. The login page will open in a new tab. After logging in you can close it and return to this page.