The Cap Rate

Most real estate professionals do not use IRR, internal rate of return, calculations—they use cap (capitalization) rates to compare one project with another. The cap rate is an approximate assessment of ROI, return on investment, as all financial measures are anyway. But they are more approximate than the IRR is, in my view. Nevertheless, it’s a handy first order of magnitude measure. The cap rate can be determined by simply dividing the net operating income, NOI, of a property by its sale price, purchase price or fair market value.

One way to look at the inverse of cap rate is that it is an approximation for the number of years it will take you to earn back your capital. It is widely used especially in the commercial real estate sector. The higher the cap rate, the better it is for a buyer and the worse for a seller.

Another way to look at the cap rate is that it is a rough measure of your rate of return on the project—it measures the rate of cash return on the overall project not your equity (unless you finance 100% of the property with equity).

Cap rates are calculated this way.

Cap rate = NOI/FMV

Where NOI = gross income for the entire project less operating costs, property taxes, utilities, repairs, maintenance, insurance and other landlord costs but before mortgage principal and interest debt repayment.

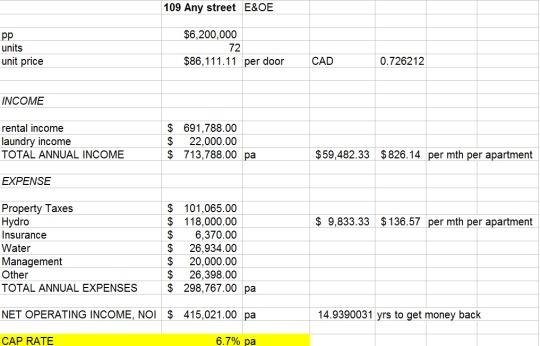

Here’s an example for an apartment building (based on a real case study):

The easiest way to understand a cap rate is this—pretend you are a rich dude for a moment and you bought 109 Any street for $6.2 million in cash… ie, you didn’t need a loan. You found the millions you needed to buy this 72 unit building in your couch.

After paying all your costs, you end up with $415,000 every year to spend on whatever you want. It’s your cash-on-cash ROI.

“Hmm,” you say, “not all that impressive.”

But what if you had saved up that $6.2 million and instead you had invested it in your bank account at say 1.5% pa? Well, you’d only have $93,000 a year to spend.

Skill testing question—which is better? $93,000 a year or $415,000?

But your cap rate does not include all the different types of returns from real estate—there is no allowance for paydown of your mortgage[1] (the wealth effect I talked about above) or real estate inflation.

You don’t get any inflation protection from having your cash in the bank but you do when you own real property.

In Ottawa, house prices in 2016 accelerated by around 2%[2], in Toronto, by a crazy 20%[3], and in many cities across North America by anywhere from 1% to, well, Toronto-style numbers (particularly in desirable places to live and work like Boston, Seattle, Portland, San Francisco and Vancouver.)

Anyway, let’s use 5% for real estate inflation, which means you also get an increase in fair market value each year of around $310,000 on your 109 Any street building. Now that buys you a lot of eggrolls if and when you refinance your building and take out some tax-free cash.

The cap rate does not take into account all the different returns you can make in real estate, which is why professional investors use IRRs. Think of the IRR as a kind of weighted average of cash on cash return, principal paydown, and real estate inflation.

[1] There

would be no wealth effect in the example I’m using here since you didn’t “need”

a mortgage to buy 109 Any street…

[2] Thinking of buying a home in Ottawa in 2017?

Here’s a price comparison, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/ottawa/ottawa-home-price-forecast-2017-comparison-1.3887110.

[3] Average GTA home price jumped 20% in 2016,

Toronto Real Estate Board credits strong economy and low interest rates for

climb in sales, https://www.thestar.com/business/2017/01/05/average-gta-home-price-jumped-20-in-2016.html.

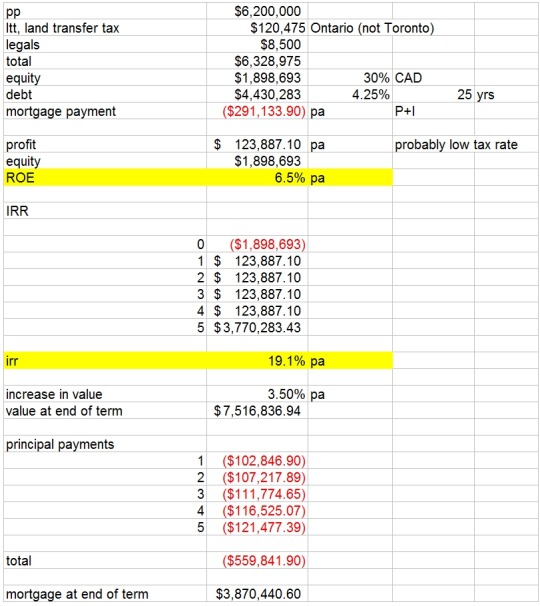

Here’s the IRR calculations we did before the purchase of 109 Any street:

…

You should remember that you make money in real estate when you buy not when you sell, so buy smart.

That means you buy when everybody else is selling (ie, when cap rates are high and interest rates are usually at their highest as well so it’s a buyer’s market) and sell when everyone else is buying (ie, when cap rates are lowest and interest rates typically lowest too). A simpler way to put it is: “Buy low, sell high.”

Now this is easier said than done. People are very sheep-like. We like to buy when everyone else is buying and what everyone else is buying. Ever bought a suit and had the salesperson tell you: “This is really in this season—everyone who is anyone is buying this.” They tell you this because it works.

It’s hard to buy real estate when no one else is and interest rates are high. Everyone will tell you not to—your CFO, your auditor, your bank, your spouse, your BOD (board of directors), your CAO, COO, even your CTO (chief techie), your buddies at the gym, will not want you to—she or he will want more dough for their department instead—it’ll have a better ROI, or so they will tell you. But you are the CEO (of your own life) and, at the end of the day, the decision is yours.

The best deals I ever did[2] were when real estate markets were depressed. I bought some land in Ottawa near a major, east-end shopping center in 1983 when interest rates were 18%. The land cost me $1 per square foot for ten acres. In 1984, I got an offer for the land at 50 cents a square foot—I thought I was in real trouble. But I went to my dad and he reminded me about rule number 1—buy low/sell high and I declined the offer.

By 1985/86, interest rates were down by half and I sold four acres for $10 per square foot to an auto dealer and the other six acres to an industrial company for $12. We made about $4m in three years on an investment of $450k; you don’t need to do an IRR or ROE calculation on deals like this—they are good deals. (That money too later found its way into the Ottawa Senators and the Palladium, now Canadian Tire Centre. Money in NHL hockey seems to go on a one-way trip—in, never out.)

In 1994, the real estate biz was again in a slump. These down cycles seem to come about every seven years and real estate tends to lead the national economy into a recession and lag it coming out which means it usually lasts longer than the general recession. But when real estate bounces up, it bounces in a hurry and you have to start selling right away if you want to time the market.

I bought 60 acres of industrial land in Kanata (west end suburb of Ottawa) for just 15 cents a square foot. I couldn’t believe it—people were just giving the stuff away—prices were lower than at any time since the Great Depression of the 1930s for goodness sake. By 1999, in a subsequent tech boom, serviced industrial land in Kanata was selling for $6 to $8 per square foot, if you could find it. Imagine going from 15 cents to say $7 a square foot on 60 acres? Now that’s real dough.

…

[1] There would be no wealth effect in the example I’m using here since you didn’t “need” a mortgage to buy 109 Any street…

[2] If only I’d stuck to real estate and not gotten into NHL hockey and other involvements… I’d be a LOT richer.

Most real estate professionals do not use the IRR, Internal Rate of Return (but probably should)—they use Cap Rates to compare one project with another. The Cap Rate (‘Capitalization Rate’) is an approximate measure, as all financial measures are anyway. But they are way more approximate than the IRR is. Nevertheless, it’s a handy first order of magnitude measure. The Cap Rate can be determined by simply dividing the Gross Operating Income of a property by its Selling Price.

One way to look at the inverse of Cap Rate is that it is an approximation for the number of years it will take you to earn back your capital. It is widely used in the commercial real estate sector. The higher the Cap Rate, the better it is for the Buyer and the worse for the Seller.

Another way to look at the Cap Rate is that it is a rough measure of your rate of return on the project—it measures the rate of return on the overall project not your equity (unless you finance 100% of the property with equity).

For a project with financing that is provided by both equity and first mortgage, we can determine the Cap Rate as shown below.

Cap Rate = ROR, where ROR is the Rate of Return for the entire project.

ROR = (NOI + CRF (i, A) x (Selling Price or Purchase Price– Equity))/Selling Price or Purchase Price, where NOI is the Net Operating Income, CRF is the Capital Recovery Factor, i is the cost of borrowing and A is the amortization period.

Thus,

Cap Rate = (NOI + CRF (i, A) x (Selling Price – Equity))/Selling Price. Basically, the NOI + CRF (i, A) x (Selling Price – Equity) is the Gross Operating Income for the project.

If the Amortization period approaches infinity, the CRF = i. In this case, we can say that the Cap Rate can be calculated as follows:

Cap Rate = (NOI + i(S.P. – E))/ S.P.

As the Equity in a project approaches zero (100% of financing is debt), we can calculate the Cap Rate as follows:

Cap Rate = (NOI + i x S.P.)/ S.P.

But NOI will be zero if E = 0 assuming that the selling price is jacked up to the point where all income is used to support debt. In that case, we have:

Cap Rate = (i x S.P.)/ S.P., for E approaching zero and NOI approaching zero or Cap Rate = i. Q.E.D.

What we have done in typical engineering fashion is to look at the boundary conditions for our formula and discovered that under certain circumstances, the Cap Rate is simple equal to the cost of borrowing. This gives you a first order of approximation for determining a Cap Rate for a project and explains, in part, why real estate is so sensitive to changes in interest rates.

The higher interest rates are, the higher the Cap Rate will be and, hence, the lower selling prices will be. The opposite is also true. Obviously, Buyers want to purchase property with the highest possible cap rates and Sellers want to sell at the lowest possible cap rates.

Real estate is highly cyclic and moves largely with interest rates. As we found out above, higher Cap Rates imply lower Selling Prices but, by definition, it also means lower Purchase Prices.

Do you want to make money in the real estate business?

Then buy when everybody else is selling (i.e., when Cap Rates are the highest and interest rates are the highest) and sell when everyone else is buying (i.e., when Cap Rates are the lowest and interest rates are the lowest). A simpler way to put it is: “Buy low, sell high.”

Now this is easier said than done. People are very sheep like. We like to buy what everyone else is buying. Ever bought a suit and had the sales person tell you: “This is really in this season—everyone who is anyone is buying this.” They tell you this because it works.

It’s hard to buy real estate when no one else is and interest rates are high. Everyone will tell you not to—your CFO, your auditor, your bank, your spouse, your BOD (Board of Directors), your CAO, COO, even your CTO (Chief Techie) will not want you to—she or he will want more dough for their department instead—it’ll have a better ROR, or so they will tell you. But you are the CEO and, at the end of the day, the decision is yours.

The best deals I ever did (and if only I had stuck to Real Estate and not got into hockey and other distractions) were when the real estate markets were depressed. I bought some land in Ottawa near a major, east-end shopping centre in 1983 when interest rates were 19%. The land cost me $1 per square foot for ten acres. In 1984, I got an offer for the land at 50 cents a square foot—I thought I was in real trouble. But I went to my Dad and he reminded me about rule number 1—buy low/sell high and I declined the offer.

By 1985/86, interest rates were down by half and I sold four acres for $10 per square foot to an auto dealer and the other six acres to an industrial company for $12. We made about $4m in three years on an investment of $450k; you don’t need to do an IRR calculation or ROR or ROE on deals like this—they are good deals. (That money too later found its way into the Sens, ugh. Money in NHL hockey seems to go on a one way trip—in, but never out.)

In 1994, the real estate biz was again in a slump. (These down cycles seem to come about every seven years and real estate tends to lead the national economy into a recession and lag it coming out which means it usually lasts longer than the general recession. But when real estate bounces up, it bounces in a hurry and you have to start selling right away if you want to time the market). I bought 60 acres of industrial land in Kanata for just 15 cents a square foot. I couldn’t believe it—people were just giving the stuff away—prices were lower than at any time since the Depression of the 1930s for goodness sake. By 1999, in the tech boom, serviced industrial land in Kanata was selling for $6 to $8 per square foot, if you could find it.

A client of mine is looking at buying a building in Ottawa for his packing supplies business. He is following my advice—own your own real estate. The SodaPop Building is selling for $4.8m. His biz will occupy about half the premises and the other half he will rent out. The Cap rate for his acquisition is:

Cap Rate (SodaPop Building) = (NOI + CRF(I, A) x (S.P. – E))/ $4,800,000 = ($301,736 + $313,864)/ $4,800,000 = 12.825%.

From his point of view (as the Purchaser), this looks pretty good. Cap Rates for industrial property can easily climb to 9, 10, 11, 12 or even more which would mean a much lower cost of acquisition for Paul (not his real name).

As discussed above, another way to look at the inverse of the Cap rate is that it is a rough measure of how long it takes to get your money back. Another useful engineering approach to problems is to check your units, viz:

Inverse of Cap Rate units = $/($/yr. + $/yr.) = $/$/yr. = yr.

So Paul’s new project will take 7.8 years to return all of its capital back to Paul (his equity) and to his debt holders. That is pretty fast if you think about the average homeowner taking 20, 25 or 30 years to pay off their home mortgage which many actually never accomplish.

But Paul should be much more interested in when he gets back his equity—this means he can turn around and do something else with his equity—buy more real estate, buy more equipment for his packing supplies biz, go on a nice holiday, buy a boat, whatever.

You get an approximate time for Paul to get his money back by simply dividing his Equity by the NOI. This works out to $1.2m divided by $301,736 or roughly 4 years. The IRR is a much more precise tool but it seems that the industry is just much more comfortable with a ‘rule of thumb’ cap rate approach.

Now let’s look at the cap rate for a small investment property. Let’s use as a n example, a multi-residential building, “Langlier Place” which has 12, 1-bedroom units and 36, 2-bedroom units. Note that it is important to know whether the cap rates you are using are effectively net or gross cap rates. The cap rates calculated above used gross operating income; for small investment properties it is typical to use net operating income where NOI is found by subtracting operating costs that the owner must pay from revenues received. The operating costs do not include either depreciation or mortgage interest. This is because cap rates remove from their calculation the debt structure of the owner. Obviously, a large well funded REIT, Pen Fund or Insurance Company will have a lower COF (Cost of Funds) than a typical private investor.

Therefore, for cap rates to be useful to compare one property with another similar one (similar in terms of quality, location, age, etc.) , you need to remove the impact of different capital structures.

Langlier Place—Owner’s Pro Forma Langlier Place—Appraiser’s Pro Forma

Revenues

YEAR 1 YEAR 2 YEAR 3

Rent $688,000 $694,000 $698,000

Parking and Laundry $ 24,000 $ 24,800 $ 26,400

Total $712,000 $718,800 $724,400

Expenses

Realty taxes…………………………………………………… $ 52,800

Water………………………………………………………….. $ 9,800

Hydro………………………………………………………….. nil*

Insurance………………………………………………………. $ 7,800

Maintenance and Repairs……………………………………… $ 5,500

Painting………………………………………………………… $12,000

Supplies………………………………………………………… $ 1,300

Elevator maintenance…………………………………………… $ 1,100

Accounting and Legal…………………………………………… $ 3,000

Superintendent…………………………………………………. $ 22,000

Mortgage Payments** (Principal and Interest)………….………$404,186

Total Operating Costs…………………………………………. $519,486

Potential Gross Income

12, 1-bedroom units @ market rent of $900 each……………. $129,600

36, 2-bedroom units @ market rent of $1,325 each………….. $572,400

Sub-total……………………………………………………… $702,000

Additional Income

Parking, 42 spaces @ $55 per month………………………… $ 27,720

Laundry, 5 w/d @ $30 per month…………………………….. $ 1,800

Total Potential Gross Income………………………………… $731,520

Less vacancy allowance of 6%………………………………………….-$ 43,912

Effective Gross Income………………………………………. $687,628

Operating Costs

Realty taxes…………………………………………………… $ 52,800

Water………………………………………………………….. $ 9,800

Hydro………………………………………………………….. nil*

Insurance………………………………………………………. $ 7,800

Maintenance and Repairs……………………………………… $ 5,500

Painting………………………………………………………… $12,000

Supplies………………………………………………………… $ 1,300

Elevator maintenance…………………………………………… $ 1,100

Accounting and Legal…………………………………………… $ 3,000

Superintendent…………………………………………………. $ 22,000

Property Management (3% of Effective Gross Income).…….… $ 20,629

Total Operating Costs…………………………………………. $135,929

Net Operating Income…………………………………………. $204,914 Semi-Net Annual Operating Income………..…………………. $551,699

Selling Price…………………………………………………. $6,500,000

Cap Rate…………………………………………………….……..8.49%

(* Paid by Tenants.)

(** Mortgage is a Canadian mortgage of $4.2 million with an interest rate of 7.25% and amortization period of 20 years.)

You will notice that the Cap Rate for Langlier Place is calculated using a ‘semi-net’ operating income. This shows how difficult and seat-of-the-pants Cap rates can be. As long as you know how the cap rate you are being quoted was used, this can be a useful way to compare one property with another. But what if someone is using NOI and someone else is using a semi-net number and someone else is using gross income? Use cap rates carefully.

@profbruce

@Quantum_Entity

Session expired

Please log in again. The login page will open in a new tab. After logging in you can close it and return to this page.